ENERGY GENERATION BY ADEPTS

By William C Bushell

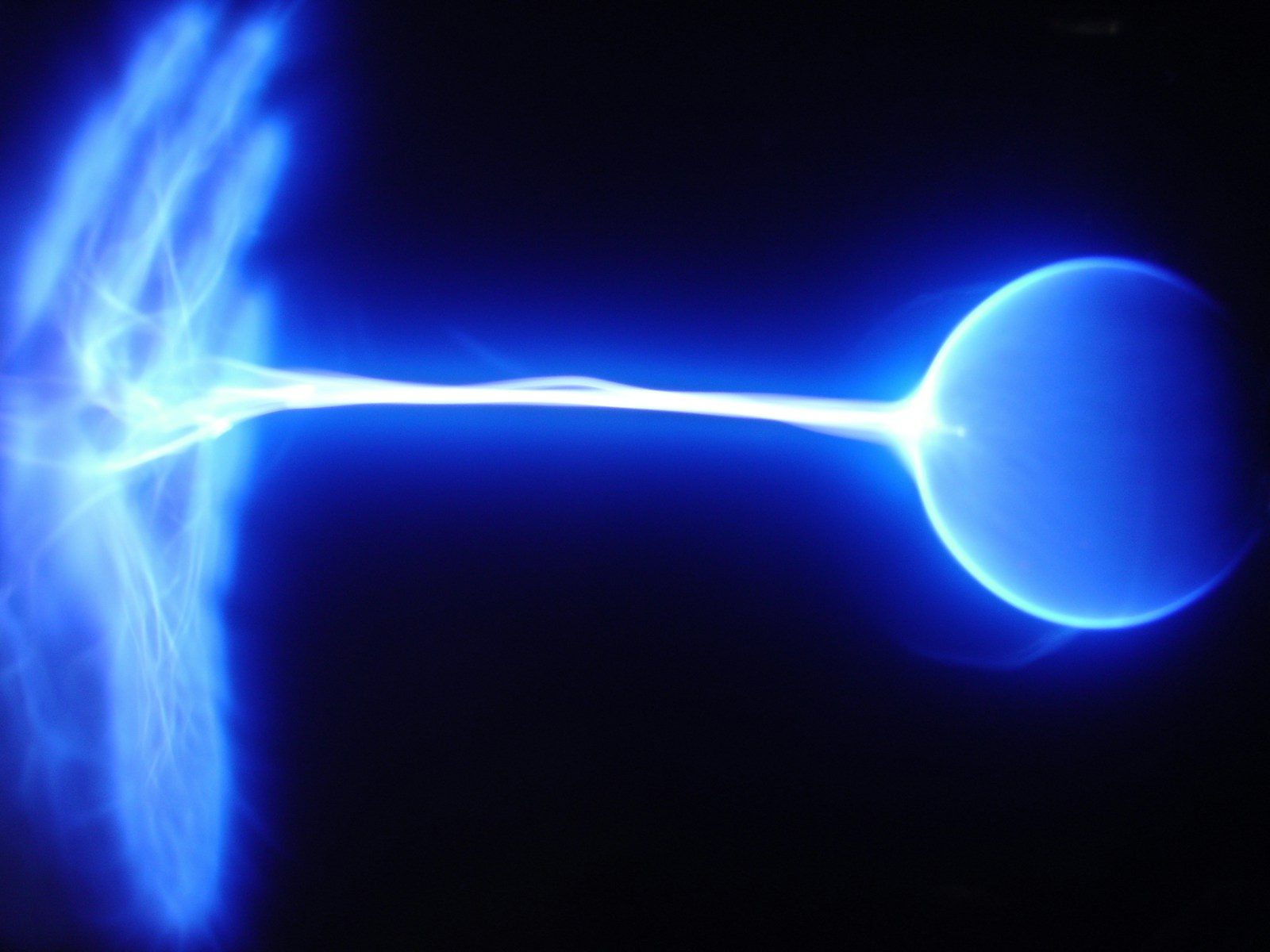

Last week we described the demonstrations of extraordinary phenomena of an apparent bioelectric nature by adepts of East Asian Taoism-based yoga practices such as the Mo Pai and related lineages. These included producing shocks and tremors in volunteers solely through touching by the hands of the practitioners, responses that were clearly identified as electrical in nature, and quite intense, by the recipients; and, as noted, these demonstrations have been recorded on film and video (see installment 18). Before proceeding to the more in-depth discussion of the implications of these demonstrations for the achievement of a range of radical, higher level enhancements of human physiological and neurobiological functioning – within the context of the “bioelectric revolution” in the life sciences and human health sciences – we will first look more closely at the psychophysiological “mechanisms” fundamental to the demonstrations. According to the scientific model in development and outlined in this series, these mechanisms include (1) achieving direct sensory awareness of the relevant physiological processes, which are typically not accessible to sensory awareness in would-be practitioners; and (2) achieving some degree of control over the processes by the practitioners, such as those (apparently) observable in the demonstrations (and of course ultimately subject to rigorous scientific scrutiny).

In the first place, we recall from earlier installments that human sensory perceptual capacities are of a far greater magnitude than generally recognized – and even of a far greater magnitude than scientifically recognized – at least until recently (see above, particularly installment 13, and Bushell 2009, 2015; Bushell & Seaberg 2018-2019; Bushell, Stern, Seaberg 2020; Carpenter 2018). As described above, meditative states such as those produced by mindfulness in conjunction with deep relaxation, can profoundly lower general psychological and physiological activity, or “noise”, leading to an increase in “the signal-to-noise ratio”, in turn allowing for the emergence of internal sensations, including those of desired areas and processes of the individual’s own body. These include a wide range of categories of somatosensory awareness, including tactile, kinesthetic, haptic, proprioceptive, and other forms of visceral awareness and interoception (Bushell 2009, Bushell et al, in progress). With practice, individuals – including most prominently adepts – are capable of achieving sensory awareness in some cases down to the atomic level, in terms of some phenomena, as described above, when such states of mindful awareness are attained. As more thoroughly reviewed in installment 13 and the references therein:

“When this kind of state is achieved, strikingly clear access to such phenomena is possible, over time, with practice. It is possible to gain conscious access to, and thereby some control over, local or regional blood flow, temperature, metabolic activity (these three of course closely related), and other forms of autonomic nervous system-controlled functions. Individuals may learn to control the behavior of single motor neurons (Smith et al 1974); skin temperature differences within a diameter of several millimeters (Kojo 1985)…[and] in addition, using an analogous program of increasing the S/N ratio, and with practice, normal subjects can learn the tactile discrimination of a single layer of molecules (Carpenter et al 2018; Bushell & Seaberg 2018-2019).”

Adepts of the Mo Pai describe using such kinds of meditative techniques to achieve awareness of what are initially very subtle sensations of bioelectricity in the abdominal region (see installment 18). In our model-in-progress we have proposed that this particular sensory awareness may (among other things) resemble the “tingling” sensations associated with the activation of the energy channels associated with acupuncture, sensations called “de qi” (see Leung et al 2006; Hui et al 2007; Ahn et al 2008; Jung et al 2016).

Awareness of internal organs has been found to accompany focused attention directed to them with practice, and with further application of the mental/multisensory imagery of activation to these organs, it is possible to increase blood flow, and thereby actual metabolic activation, to internal organs. In the scientific research that has been conducted, these organs have included the gonads, the spinal column, abdominal organs such as the lungs and liver, the brain, and the pineal gland, among others (see reviews of data in Bushell 2009, 2015; Bushell, Stern, Seaberg 2020; Bushell et al, in progress; Villien et al 2005; Luthe & Schultz 1969-1970; Stetter & Kupper 2002). Our model in-progress suggests that, as in the case of metabolic activation, such techniques may also lead to the initial awareness, activation, and amplification of – and eventually some degree of control over – endogenous bioelectrical activity.

Observations of, and interviews with, these adepts (and adepts-in-training) have additionally indicated that kinesthetic imagery in particular may play a significant role in the guiding of this “accessed” bioelectrical energy out from the abdominal cavity, up to and through the arms, and out through the hands (Bushell, field notes; Bushell et al, in progress; and see description of the relevant psychophysiological principles of the workings of kinesthetic mental imagery in Ridderinkhof & Brass 2015; Weng et al 2021).

In the next installments we will utilize our developing scientific model to bring further cohesiveness and comprehensiveness to this wide-ranging psychophysiological and anthropological data, and to integrate it with the brand new scientific findings from the exploding field of bioelectricity, especially in turn focusing on the subject of the further reaches of true human potential.

References

Ahn AC, Colbert AP, Anderson BJ, Martinsen OG, Hammerschlag R, Cina S, Wayne PM, Langevin HM. Electrical properties of acupuncture points and meridians: a systematic review. Bioelectromagnetics. 2008 May;29(4):245-56. doi: 10.1002/bem.20403. PMID: 18240287.

Bushell WC, 2015 (Bushell WC, Lederberg J, 1999). Summary of communications with Nobelist Joshua Lederberg on “Focused Visualization for Treatment of Wound Infection by Staph Aureus and Other Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens” (letter, published by National Library of Medicine https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101584906X13080-doc); Anthropology Department, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Bushell WC, Seaberg M, 2018-2019. Experiments Suggest Humans Can Directly Observe the Quantum, The Sensorium, Psychology Today.

Bushell WC, Stern E, Seaberg M, 2020. Yoga and Meditation, Sensory Health, and COVID-19. Psychology Today (online) (https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/sensorium/202007/yoga-and-meditation-sensory-health-and-covid-19).

Bushell WC 2009. Integrating Modern Neuroscience and Physiology with Indo-Tibetan Yogic Science, in (EA Arnold, editor) As Long as Space Endures: Essays on the Kalachakra Tantra in Honor of H.H. the Dalai Lama. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Press.

Carpenter CW et al, 2018. Human ability to discriminate surface chemistry by touch, Materials Horizons 5: 70-77.

Hui KK, Nixon EE, Vangel MG, Liu J, Marina O, Napadow V, Hodge SM, Rosen BR, Makris N, Kennedy DN. Characterization of the “deqi” response in acupuncture. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007 Oct 31;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-33. PMID: 17973984; PMCID: PMC2200650.

Jung WM, Shim W, Lee T, Park HJ, Ryu Y, Beissner F, Chae Y. More than DeQi: Spatial Patterns of Acupuncture-Induced Bodily Sensations. Front Neurosci. 2016 Oct 19;10:462. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00462. PMID: 27807402; PMCID: PMC5069343.

Leung AY, Park J, Schulteis G, Duann JR, Yaksh T. The electrophysiology of de qi sensations. J Altern Complement Med. 2006 Oct;12(8):743-50. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.743. PMID: 17034280.

Luthe W, Schultze JH, Autogenic Therapy, 6 vols. 1969-1970. New York: Grune & Stratton.

Ridderinkhof KR, Brass M. How Kinesthetic Motor Imagery works: a predictive-processing theory of visualization in sports and motor expertise. J Physiol Paris. 2015 Feb-Jun;109(1-3):53-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2015.02.003. Epub 2015 Mar 25. PMID: 25817985.

Stetter F, Kupper S, 2002. Autogenic training: a meta-analysis of clinical outcome studies, Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 27(1): 45–98.

Villien F, Yu M, Barthélémy P, Jammes Y. Training to yoga respiration selectively increases respiratory sensation in healthy man. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2005 Mar;146(1):85-96. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.11.010. PMID: 15733782.

Weng HY, Feldman JL, Leggio L, Napadow V, Park J, Price CJ. Interventions and Manipulations of Interoception. Trends Neurosci. 2021 Jan;44(1):52-62. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.09.010. PMID: 33378657; PMCID: PMC7805576.